Black History Month: 9 Hair Industry Innovators Who Made Major Waves

Published Feb 5, 2024

Have you ever noticed the design of your hairbrush? Or examined the construction of your curling iron? If you look at your hair care stash, you’ll probably notice an array of products.

Your hair care favorites involve over a century of innovation moved forward by historic Black leaders. Their momentous inventions have paved the way for countless brands, formulas, methods, and tools used today.

The work of Black inventors and entrepreneurs persevered despite the exclusions of the beauty industry at the time, creating jobs and furthering education for thousands of Black Americans.

This year, we are celebrating Black History Month by sharing the inspiring stories behind Black trailblazers who transformed the hair industry. Meet the women moguls who cut though barriers and conditioned future change-makers to create a better future.

Annie Malone

Annie Malone

Inventor, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and one of America’s first female self-made multimillionaires, Annie Malone revolutionized the hair care industry for Black women, paving the way for future beauty entrepreneurs.

Growing up, Malone enjoyed chemistry, but withdrew from school due to frequent illnesses. She became enthralled with hair care and developed a homemade line of products for Black women—did I mention she was only 20 years old?

While many women damaged their hair with harmful straightening methods, Malone pioneered non-damaging products that flattened strands and promoted regrowth.

Her hero product, “Wonderful Hair Grower” was a growth stimulant, which attracted significant popularity and would later inspire a similar product by Madam C. J. Walker (one of Malone’s sales recruits).

Malone also pioneered an agent system, where she would hire and train women to serve as salespeople—they would then recruit others to join throughout the country and beyond. This spawned mass distribution of her brand throughout the U.S., South America, Africa, and the Caribbean.

In addition to hair care, she also launched cosmetic items including lipstick, cold cream, and powders in a variety of shades. Malone began using the name “Poro” to trademark her successful products and hair/scalp nourishing system, which earned her status as one of America’s wealthiest women.

With her incredible fortune, Malone focused on giving back by donating to universities, the YMCA, Black orphanages throughout the country and more.

In 1918, she built a million dollar complex that housed a factory and cosmetics school. Poro College served as training grounds for Black women, offering employment, lodging and education in their quest for financial independence. The space also provided a meeting place for Black organizations and individuals who were unable to access most public areas at the time.

Madam C. J. Walker

Madam C. J. Walker

Born “Sarah Breedlove” to parents who were formerly enslaved, Madam C. J. Walker once worked as a washerwoman making a mere $1.50 a day. Persisting, she became a self-made millionaire through her wildly popular line of hair care.

Breedlove experienced hair loss, dandruff, and other scalp ailments, which were unfortunately very common among Black women during the 1890s. Due to a lack of indoor plumbing, many Black families were unable to regularly shampoo to address lice and other pollutants.

Breedlove decided to channel her efforts by experimenting with home remedies, treatments, and products—few of which were, on their own, tailored to her hair texture.

In the early 1900s, Breedlove moved to Colorado and began working for Annie Malone as a sales agent, all while gaining vital hair care knowledge that she would later incorporate into her own line. She also married Charles Walker and became professionally known as Madam C. J. Walker.

Following in Annie Malone’s footsteps, Walker invented a formula for hair growth and scalp conditioning, founded her own business, and began manufacturing and selling her own products.

Motivated by healthy hair growth, Walker developed a special hair care method featuring her shampoo, hair grower, oil, hot combs, and more to deliver soft, conditioned strands.

Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company employed about 20,000 women as sales agents. She offered sales training as well as guided women toward building their own businesses and becoming financially secure.

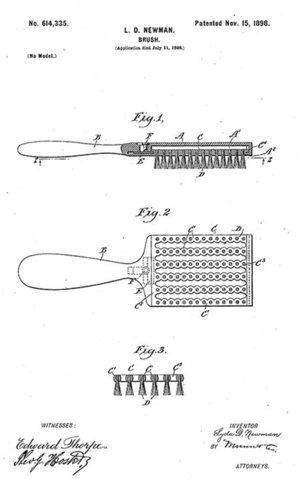

Lyda Newman

Women’s rights activist and inventor Lyda Newman patented a new and improved hairbrush design—at just 13 years old.

Growing up, Newman moved to New York City from Ohio. She began working as a hair specialist and identified the need for a more user-friendly way to fix her clients’ hair—it all came down to the brush.

In 1898, she patented a brush specifically designed for Black women’s hair with a carefully constructed compilation of firm, synthetic bristles (most brushes during this time were made with animal hair). Not only did these bristles last longer, they were evenly spaced for easy cleaning.

The innovative design promoted ventilation for quicker drying and featured a removable compartment to conveniently catch dirt and debris. Plus, the synthetic materials made the brush easier and cheaper to manufacture, as well as more affordable and accessible to women.

If it weren’t for Newman’s invention, we would not have most of the brush designs we know and love today.

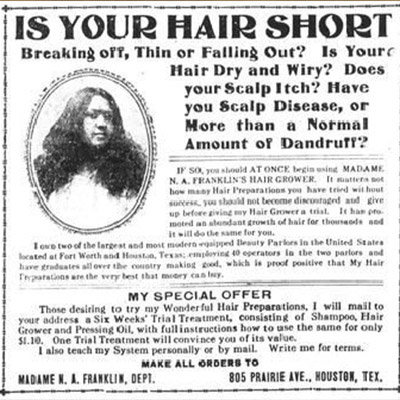

Nobia A. Franklin

Nobia A. Franklin

Inspired by the preceding beauty moguls, Nobia A. Franklin developed homemade hair products and began her career by opening a salon inside of her San Antonio home. In 1916, the Texas-born beautician and entrepreneur opened a salon in Fort Worth. Shortly after, she founded the Franklin School of Beauty Culture in Houston.

By the early 1920s, nearly 500 students had graduated from her beauty school ready to pursue careers in cosmetology. Her teaching and guidance made it possible for women to make an independent living by mastering her system of beauty.

Franklin’s company offered a wide range of products, including hair growth formulas, tonics, pressing oil, soaps, special trial treatments (only $1.10!) and face powders.

Her school was considered the largest African American beauty school in the southern United States, pre-desegregation. The space remains in operation as the oldest operated beauty school in Texas.

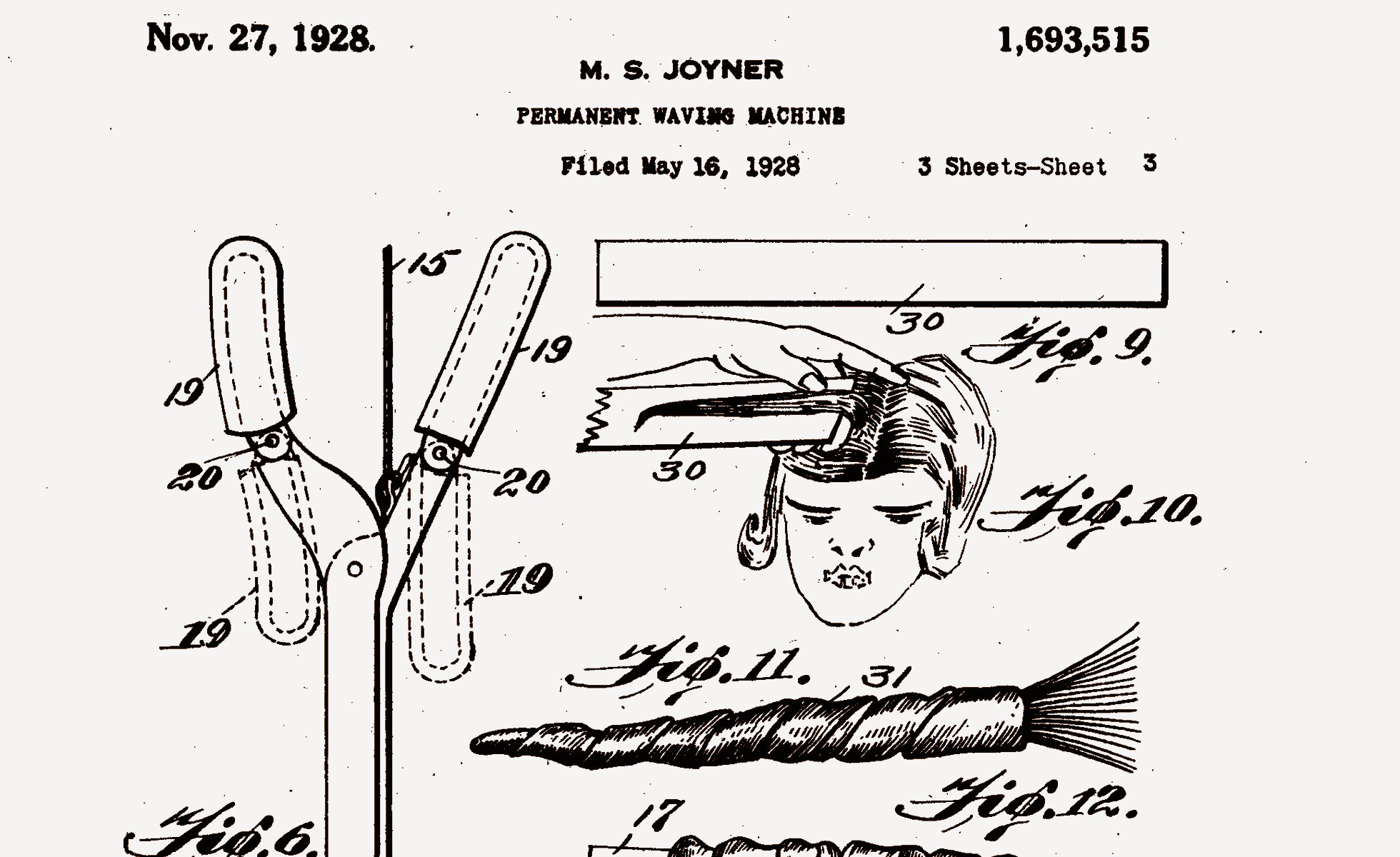

Marjorie Joyner

Marjorie Joyner

From making waves in the hair industry to fighting racial injustice in the U.S., Marjorie Joyner changed the course of beauty and American history throughout her 98 years of life.

Joyner’s passion for beauty blossomed when she graduated from A.B. Molar Beauty School in 1916. After graduation, she opened her own salon in Chicago where she met Madam C.J. Walker, whom she would later work for as a national adviser.

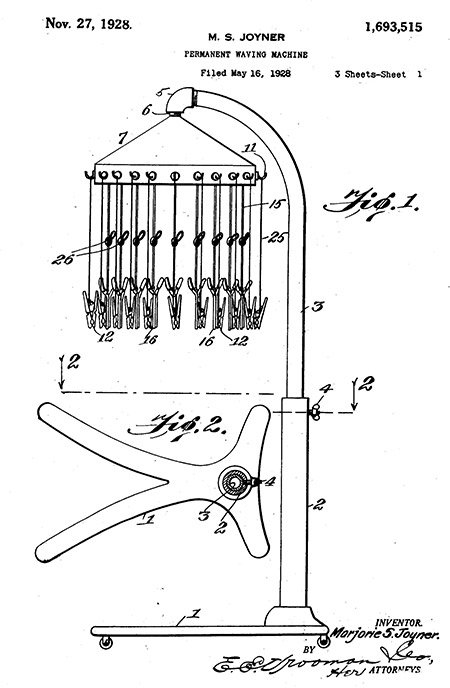

In 1928, Joyner would revolutionize the cosmetology industry forever with a hairstyling invention inspired by cooking a pot roast. While cooking, she would use rods to warm the meat from the inside and believed that a similar heating process would effectively keep hair curls intact.

Joyner envisioned wrapping hair around rod-like apparatuses for hands-free curls in just one sitting—a better alternative to lengthy, section-by-section styling with conventional hot tools.

She soon created and patented the “Permanent Waving Machine,” which consisted of multiple rods connected to a drying hood by electrical cords. The device was immediately welcomed into salons, and women would sit under the drying hood to set their style for great hair that lasted for days.

Joyner’s career began to heat up with the success of the wave machine. She went on to co-found the United Beauty School Owners and Teachers Association and start the Alpha Chi Pi Omega Sorority and Fraternity (a historically Black organization for beauticians and barbers).

Throughout her leadership, she taught around 15,000 stylists, helping them gain respect and success in the growing field.

What really drove Joyner was her passion for making significant change, not just for Black beauticians, but also for all Black women enduring racial discrimination during the 1930s.

Working alongside First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Joyner became a leader on the Democratic National Committee where she advised New Deal agencies in their outreach to Black women, as well as helped found the National Council of Negro Women.

Sara Spencer Washington

Little did Sara Spencer Washington know that her one-room beauty shop in New Jersey would grow into a bustling empire, securing her influential place in beauty history.

Starting out as a hairdresser, Washington found herself constantly experimenting with ingredients and products that catered to a growing market of Black women. She would work in her salon by day and focus on product development and sales after hours.

Around 1920, her small business flourished into a newfound venture, the Apex News and Hair Company. She sold a variety of products ranging from hair care to perfumes, creams and lipsticks with advertisements celebrating Black style and culture.

The vast success of her brand allowed for expansion into Apex Beauty Colleges, Apex Laboratories, Apex Publishing Company and more. Her empire included 11 beauty schools in the U.S. alone, in addition to several schools abroad.

Along with employing thousands of Black women (at one point there were 45,000 Apex agents nationwide), Washington’s recognition as one of the world’s top businesswomen at New York World’s Fair of 1939 helped bring international recognition to the impactful contributions of Black women.

Rose Morgan

Rose Morgan

Rose Morgan technically became a businesswoman at 10 years old. She would go door-to-door selling paper flowers to her neighbors for five cents a bunch. Her early business prowess would blossom into ownership of the largest beauty parlor for Black Americans in the world.

As she grew up, Morgan shifted from flower creation to her newfound passion—hairstyling.

In 1938, she received her big break: styling actress and singer Ethel Waters’ hair. She used her special technique that involved applying product sparingly for silkier results with more bounce. With just $500 to her name, Morgan moved to New York and began renting a booth in Upper Manhattan, which quickly brought a steady flow of clients.

In 1945, she opened her own salon, Rose Meta House of Beauty, which would amass over $3 million in sales over a few short years. The hair salon expanded its offerings to include massages, skin care, and other services that were not afforded to Black women at the time.

With coat-check available, Morgan’s elegant space was a tranquil oasis where women could experience relaxation and pampering without lifting a finger. She ensured that Black women, who were so accustomed to taking care of others, would be well taken care of and treated with respect in her salon.

In 1955, Morgan bought a brand new building, called Rose Morgan’s House of Beauty that included a dressmaking department, charm school, salon facilities and later a wig salon. Throughout her career, she employed and trained over 3,000 people to work in her massive beauty institution.

Christina Jenkins

Christina Jenkins

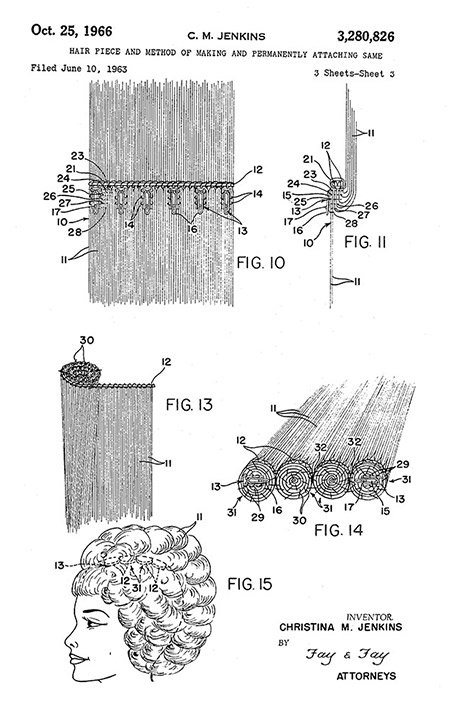

Christina Jenkins developed the sew-in hair weaving technique, a giant leap for the hair industry.

In 1943, Jenkins graduated college with a Bachelor’s Degree in Science and began working for a wig manufacturer in Chicago. While researching a technique to firmly secure wigs without the use of heat and harsh chemicals, she came up with a groundbreaking idea.

She believed that combining commercial hair and natural hair would yield longer, more voluptuous results. Jenkins’ hair weaving technique involved braiding cornrows on her clients, then affixing commercial hair to a net, which was then sewn onto the cornrow base.

In 1951, she received a patent for her historical method still used by stylists worldwide.

Theora Stephens

While there is little information available about Theora Stephens, her 1980s patent for a new and improved “pressing and curling iron” revolutionized hair-twirling techniques.

As a hairdresser, Stephens sought out to improve outdated curling techniques. Her design, which closely resembles the irons we know and love today, featured a spring to press and hold curls for easy styling and longer-lasting results.

Read more: 5 Historic Black Leaders Who Changed the Cosmetics Industry for the Better

This article was originally published February 10, 2021