Beauty History Lesson: The Art of Victorian Hair Jewelry

Published Apr 2, 2014

Would you ever wear jewelry made from human hair? Something that may seem creepy really isn’t at all, especially considering the fact that wearing other people’s hair on our heads is a pretty normal thing (in the form of natural hair weaves, extensions, and wigs).

But in the 1800s, so-called “hair jewelry” was big—that is, decadent necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and pendants fashioned partially, if not entirely out of, human hair. And not just any human hair. Usually, these accessories were made with the locks of a loved one, dead or alive.

Hair jewelry got really popular in the mid-1800s, but the craft dates back to Shakespearean times and probably even earlier than that—there are Egyptian tomb paintings that appear to depict scenes in which pharaohs and queens exchange balls of hair as tokens of love. Often, people created these accessories as a way to mourn the loss of a friend, family member, or lover: like ashes, strands of hair were kept as a symbol of remembrance, and assembled into intricate jewelry pieces. It’s written that Queen Victoria wore a piece of jewelry made with her husband Prince Albert’s hair, every day after his death. Because of the Queen’s influence, mourning jewelry stayed in fashion until the end of the 19th century. Call it grieving in decadence.

Of course, mourning was only part of the draw to the delicate craft. Many Victorian era fans of hair jewelry would craft keepsakes from the hair of their lovers or children, and some used their own hair to make pieces to be given away as gifts.

There were two methods for working with the precious strands. “Palette worked” jewelry involved laying small, curled locks flat and gluing them to a base—the designs were then set in a small gold or silver frame behind crystal or glass. The hairs were often decoratively layered and shaped to look like feathers, flowers, or even landscapes. Most palette work was done on a small scale (say, somewhere between a quarter-inch to two inches in diameter). The pieces weren’t always so elaborate; sometimes they were made of a simple braid or coil woven from the lock of hair.

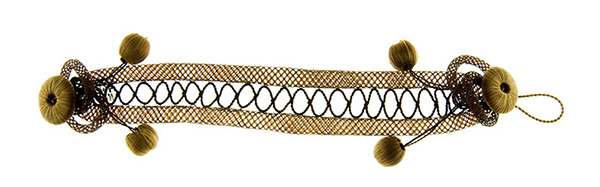

The “table worked” method was more detailed, and appears to have roots in Scandinavia. It involved weaving hair like lace using a special table and technique similar to bobbin weaving. The woven net-like hair would then be used as cording for a bracelet or stiffened and formed into delicate beading for earrings or a necklace. The craftsmanship on table worked pieces is mindblowing.

It’s also common to find hair jewelry that incorporates hair from two or more people. Often these locks were plucked from members of the same family, and worn by a mother or grandmother as a token of love. An early (and much more complex) version of the family photo wallet, perhaps?

Hair jewelry as a pastime became really popular by 1850—with both men and women creating pieces themselves. But still, it wasn’t cheap, or even free. Setting and finishing a piece still required a pricey trip to a jeweler or goldsmith. For this reason, hair jewelry was generally only worn by the wealthy.

As the popularity of hair jewelry grew through the 19th century, people began to steer away from the practice of using the hair of friends and family, and opted for anonymous hair bought from tradesmen. Peasants would sell or trade their hair to dealers, who would then resell to enthusiasts looking to fashion it into decorative accessories.

Today, you can find hair jewelry and accessories in museum collections such as the Bangsbo Museum in Denmark, online at the Minnesota Historical Society, hairworksociety.org, and often at antique sales. What’s really incredible about human hair is how resilient it is to aging: strands trimmed from our heads can last thousands of years without disintegrating, making it what is perhaps one of the most durable crafting materials on earth. Think about it: our own hair is capable of outliving us ten times over!

Beautiful hair. Beautiful hair jewelry. Leave it to history to help us expand our ideas of showcasing our lustrous locks!

All photos courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society ©.

You Might Also Like

-

Hair

Loathe or Love: Hair Tattoos

- 58

-

Tips & Tricks

New Hairdo? Make The Most Of It With These Makeup Tweaks!

- 1411

-

Hair

Hairstyles We Loved from Pitchfork Music Fest 2013

- 138

-

DIY

Two-Ingredient DIY Coconut Hair Treatment

- 2402

-

Hair

Define Your Curls and Waves

- 117

-

outFit with Kit

Body By Kit: Is Too Much Protein Making You Fat?

- 169

-

Hair

Cannes Film Festival Hair: Elizabeth Olsen

- 22

-

Hair

Beach Hair Styling Tips

- 790